Non resta nulla. Barche vita mia

(m/y Nidas in navigazione – foto gentilmente concessa da Alfredo Tessi)

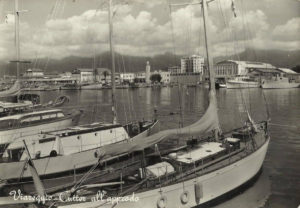

Tutti i veicoli d’epoca che ho usato per i miei spostamenti erano italiani e degli anni ’50. Anzi no, uno era inglese. All’epoca mi muovevo spesso. Quando riuscii a comprarmi una barca, pensai che ce l’avevo fatta, ero davvero felice; quella barca, proprio lei, l’avevo vista molto tempo prima e me ne ero innamorato al primo sguardo, subito. Tutte le barche a bordo delle quali sono salito o che ho guardato a lungo da piccolo e anche dopo, dalle banchine sulle quali ho passato le ore più felici della mia adolescenza, sono rimaste impresse nei mie occhi e nel mio cuore; ne ricordo minuziosamente e con emozione ogni particolare delle linee degli scafi, la distribuzione delle sovrastrutture, oblò, occhi per guardar loro dentro, sartie e crocette degli alberi, la bellezza di bozzelli in legno in schooner inglesi degli anni ’10 e ’20 del novecento, la riga colorata, gialla o blu, delle loro linee di galleggiamento, le vele, i dettagli della poppa, l’imponenza e snellezza degli alberi. E la girandola immobile delle eliche quando erano in secco sugli scali. Comunque, tra tutte, quelle che mi sono rimaste care come le zone più belle di quella mia età delle crescite sono la prua dritta del Sibilla e del Perry, la lunga poppa a ventaglio del vecchio motor yacht dall’aria straniera che si voleva fosse stato degli Antinori e divenne il primo bar galleggiante del porto, il Nidas, indecifrabile, forse di origini francesi, dal naso alto e lo specchio di poppa di una sottigliezza che gli faceva accarezzare la scia: e poi le linee già più flessuose e lanciate verso la modernità di Edna, del Dentale e della sua quasi gemella Qibla, del San Giorgio e del Filippo II, l’assurdità catturante del Mavì, brigantino goletta in ferro con lamiere imbullonate che coi suoi casseri, alberi, pennoni, trinchetti e doppi bompressi sembrava già pronto a portare in una comoda andatura di lasco Capitan Uncino nelle maree dipinte tra le luci sui pannelli dei flippers, a trasbordare giocatori in qualche futura, ancora sconosciuta, imminente gara digitale su percorsi ancora più luminosi, tra cosi tante nuove intermittenze di lampi e di suoni, vocine stridule, voci imperiose o nasali, meccaniche, ammiccanti o minacciose, campanelli e risa sbeffeggianti da fare invidia al fantasma di Canterville. Il Mavì: fantastica fantasiosa barca dispersa nelle luci dei ricordi non si sa in che foschie sia invece finita.

Non resta nulla… lo scafo magnifico dell’Old Fox dalle linee sinuose, che accoglievano l’occhio e lo facevano loro per sempre, un ketch di impressionante bellezza, sopravvissuto a guerre e tempeste e che adesso, gli alberi ancora eretti, il boma della maestra semi-accasciato sulla (imperterrita) coperta di teak, l’albero di mezzana ormai senza sartie ridotto a bastoncino per la girandola di un bambino, stava morendo, ancora magnifico, fiero, ancora dritto in chiglia, conscio della propria bellezza, nell’invasatura che aveva ceduto, quasi appoggiato a un muro di cinta che sembrava aspettarlo, sullo scalo più remoto di un cantiere in piena attività.

Non resta nulla.

(piccoli yacht all’ormeggio Viareggio darsena Europa fine anni 50 – cartolina)

Nothing remains. Boats, my life.

Nothing remains. Boats, my life.

All the vintage vehicles that I used for my travels were Italian and from the 1950s. Indeed, no, one was English. I used to move frequently at that time. When I managed to buy a boat I thought I had made it, I was really happy; that boat, just her, I had seen it a long time before and I fell in love with it as soon as I saw it, immediately. All the boats on board which I got on or which I looked at for a long time as a child and even after, from the quay, have remained etched in my eyes as well as in my heart; I meticulously and emotionally remember the lines of the hulls, the distribution of the superstructures, the sails, the colored line, yellow or blue, of their water lines, the details of the stern and the masts. And the motionless pinwheel of the propellers when they were out of the water on the slipways.

However, among all, the ones that have remained dear to me as the most beautiful areas of that my time of growths are the straight prow of the Sibilla and the Perry, the long fan stern of the old foreign-looking motor yacht that was supposed to have belonged to the Antinoris and became the first floating harbor bar, the enigmatic Nidas, of French origins, high-nosed and her transom to caress the wake; and then the lines already more supple and launched towards the modernity of Edna and Dentale and of its almost twin Qibla, of San Giorgio and Filippo II, the capturing absurdity of the Mavì, an iron brig schooner with bolted plates that with its masts, yards, foresails and double bowsprits seemed ready to take Captain Hook, in a comfortable slack reaching gait, from the docks and pinball machines, where he was already vanquishing rivals and competitors, to some future, still unknown imminent digital competition along even brighter paths, to get stunned, who knows, and slipping brilliantly dizzy in dives and emersions in and from so many new intermittent flashes and sounds, among shrill, nasal and mechanical winking voices, bells and mocking laughter to make the Canterville ghost envy. Mavì: fantastic imaginative boat dispersed in the lights of memories, no one knows what mists it ended up in.

Nothing remains… the magnificent hull of Old Fox with its sinuous lines, which welcomed my eyes and made them their forever, a ketch of impressive beauty, which had survived wars and storms, the masts still erect, the main sail boom half-slumped on the (undeterred) teak deck, the mizzen mast now without shrouds reduced to a stick for a child’s pinwheel, was now dying, still magnificent, proud, still straight on the keel, conscious of its own beauty, on a socket that had given way, almost leaning against the farthest boundary wall that seemed to be waiting for him, by the most remote abandoned slipway of a shipyard in full operation.

Nothing remains.

(m/y Nidas in navigazione – foto gentilmente concessa da Alfredo Tessi)

(foto del 1951 di ALCA I – costruzione cantiere Bergamini Viareggio su progetto Bergamini e dell’armatore Fausto Tessi)

(foto di Nidas e ALCA I pubblicate by courtesy of Alfredo Tessi)